March 1, 1896: Henri Becquerel Discovers Radioactivity

In one of the most well-known accidental discoveries in the history of physics, on an overcast day in March 1896, French physicist Henri Becquerel opened a drawer and discovered spontaneous radioactivity.

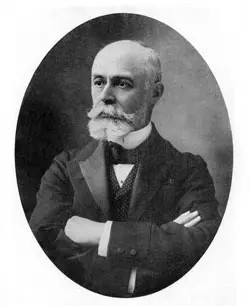

Henri Becquerel was well positioned to make the exciting discovery, which came just a few months after the discovery of x-rays. Becquerel was born in Paris in 1852 into a line of distinguished physicists. Following in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps, he held the chair of applied physics at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. In 1883 Becquerel began studying fluorescence and phosphorescence, a subject his father Edmond Becquerel had been an expert in. Like his father, Henri was especially interested in uranium and its compounds. He was also skilled in photography.

In early 1896 the scientific community was fascinated with the recent discovery of a new type of radiation. Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen had found that the Crookes tubes he had been using to study cathode rays emitted a new kind of invisible ray that was capable of penetrating through black paper. The newly discovered x-rays also penetrated the body’s soft tissue, and the medical community immediately recognized their usefulness for imaging.

Becquerel first heard about Roentgen’s discovery in January 1896 at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences. After learning about Roentgen’s finding, Becquerel began looking for a connection between the phosphorescence he had already been investigating and the newly discovered x-rays. Becquerel thought that the phosphorescent uranium salts he had been studying might absorb sunlight and reemit it as x-rays.

To test this idea (which turned out to be wrong), Becquerel wrapped photographic plates in black paper so that sunlight could not reach them. He then placed the crystals of uranium salt on top of the wrapped plates, and put the whole setup outside in the sun. When he developed the plates, he saw an outline of the crystals. He also placed objects such as coins or cut out metal shapes between the crystals and the photographic plate, and found that he could produce outlines of those shapes on the photographic plates.

Becquerel took this as evidence that his idea was correct, that the phosphorescent uranium salts absorbed sunlight and emitted a penetrating radiation similar to x-rays. He reported this result at the French Academy of Science meeting on February 24, 1896.

Seeking further confirmation of what he had found, he planned to continue his experiments. But the weather in Paris did not cooperate; it became overcast for the next several days in late February. Thinking he couldn’t do any research without bright sunlight, Becquerel put his uranium crystals and photographic plates away in a drawer.

On March 1, he opened the drawer and developed the plates, expecting to see only a very weak image. Instead, the image was amazingly clear.

The next day, March 2, Becquerel reported at the Academy of Sciences that the uranium salts emitted radiation without any stimulation from sunlight.

Many people have wondered why Becquerel developed the plates at all on that cloudy March 1, since he didn’t expect to see anything. Possibly he was motivated by simple scientific curiosity. Perhaps he was under pressure to have something to report at the next day’s meeting. Or maybe he was simply impatient.

Whatever his reason for developing the plates, Becquerel realized he had observed something significant. He did further tests to confirm that sunlight was indeed unnecessary, that the uranium salts emitted the radiation on their own.

At first he thought the effect was due to particularly long-lasting phosphorescence, but he soon discovered that non-phosphorescent uranium compounds exhibited the same effect. In May he announced that the element uranium was indeed what was emitting the radiation.

Becquerel initially believed his rays were similar to x-rays, but his further experiments showed that unlike x-rays, which are neutral, his rays could be deflected by electric or magnetic fields.

Many in the scientific community were still absorbed in following up on the recent discovery of x-rays, but in 1898 Marie and Pierre Curie in Paris began to study the strange uranium rays. They figured out how to measure the intensity of the radioactivity, and soon found other radioactive elements: polonium, thorium, and radium. Marie Curie coined the term “radioactivity” to describe the new phenomenon. Soon Ernest Rutherford separated the new rays into alpha, beta, and gamma radiation, and in 1902 Rutherford and Frederick Soddy explained radioactivity as a spontaneous transmutation of elements. Becquerel and the Curies shared the 1903 Nobel Prize for their work on radioactivity.

The story of Becquerel’s discovery is a well-known example of an accidental discovery. Somewhat less well known is the fact that 40 years earlier, someone else had made the same accidental discovery. Abel Niepce de Saint Victor, a photographer, was experimenting with various chemicals, including uranium compounds. Like Becquerel would later do, he exposed them to sunlight and placed them, along with pieces of photographic paper, in a dark drawer. Upon opening the drawer, he found that some of the chemicals, including uranium, exposed the photographic paper. Niepce thought he had found some new sort of invisible radiation, and reported his findings to the French Academy of Science. No one investigated the effect any further until decades later when Becquerel repeated essentially the same experiment on that gray day in March 1896.