A Mind Can Be Open Without Being Empty: Skepticism and Scientists

By James Trefil

Often, they will spin a story that goes like this: there was once an isolated, ignored genius who had worked out the truth about a particular scientific problem. Ignored by the scientific establishment, this individual nevertheless persevered, and long after his death his true genius was finally recognized. The usual people cited are Galileo Galilei or Alfred Wegener (the author of the theory of continental drift), and the usual purpose of the story is to invite a comparison between the way these figures were treated and the trouble the storyteller is having getting scientists to listen to his revolutionary theories about ESP, UFO's, or the origin of the universe.

Is the scientific community really closed to ideas from the lonely genius? Do the historical stories of Galileo and Wegener really show that we are willing to listen only to our own?

In fact, the Copernican theory of the heliocentric universe had been debated in the European scientific community for a century before Galileo brought it to the attention of the public with his popular books.

Even ignoring the issue of heresy, there would have been good reasons for scientists in the 17th century to reject Galileo's arguments. Most of his book Dialogue Concerning Two World Systems was taken up by an argument for heliocentrism based on a completely incorrect theory of the tides.

The story of Alfred Wegener is less familiar to most people, although the "sound bite" folklore about him is that he discovered the motion of continents early in the 20th century and was ignored, even though he ultimately turned out to be right.

In fact, Alfred Wegener was not only a respected member of the German scientific establishment, he was one of its leaders. Wegener was the director of one of his country's major research institutions.

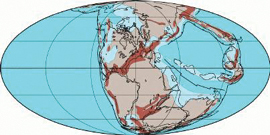

The only reason Wegener enters the mythology of science is the fact that in 1915 he published a book called The Origin of Continents, in which he suggested that at some time in the past all the land on Earth had been clumped together into one giant supercontinent, which he called Pangaea ("All Land"), and that the continents had moved ("drifted") to their present positions since then. This is the celebrated theory of Continental Drift.

The book was hardly ignored; it was debated widely in Germany.

In general, hard rock geologists opposed it and theoretical geophysicists supported it. There were two main arguments against his thesis: one centered on the fact that no one could think of a mechanism that could move the continents, while the other concerned the question of whether the data supported Wegener.

Wegener advanced five pieces of evidence that supported his thesis of continental motion.

These were (1) the fact that the coastlines of Europe, Africa, and the Americas fit together like a jigsaw puzzle, (2) the fact that some geological formation (mainly in Africa) seemed to continue across into the Americas, (3) the fact that some fossil species seemed to be found in corresponding places on both sides of the Atlantic, (4) the fact that the location of glacial moraines seemed to indicate that continents once had a different relation to the poles than they do now, and (5) the fact that two different geodetic determinations of the distance between Greenland and Europe indicated that the distance was increasing.

Hard rock geologists argued that in many cases Wegener had simply gotten the rock identification wrong?that what he called glacial moraines were nothing of the kind, for example. They also pointed out that the facts that two minerals are identical doesn't mean they were made in the same place and that, given the enormous number of geological formations in Europe and North America, it was not surprising that a few would match up.

Other aspects of Wegener's argument could be incorporated easily into the Fixed Earth theories of the time. These theories incorporated land bridges that could sink beneath the ocean, so the fossil evidence could be easily explained. They also allowed the possibility that during an earlier stage, continents could indeed have moved on a molten planet. Thus, the jigsaw puzzle fit evident on the map didn't have to imply that the continents were still moving.

Finally, the geodetic evidence was such that the error in the two measurements was larger than the claimed difference, a fact which weakened the Greenland argument considerably.

In the end, then, scientists of the 1930's and 40's were quite right to reject continental drift. So what has happened since then to change our view of the Earth?

In a word, data. Starting in the mid 1960's, data supporting the notion of continental motion started to come in. Starting with the measurements of paleomagnetic patterns on the ocean floor and extending to studies of magnetic records in sediments and rocks, a picture of a dynamic, active Earth emerged. Confronted with overwhelming data, the scientific community gave up its fixed Earth paradigm and adopted the new one in less than five years.

The theory that emerged was not Wegener's continental drift, even though it incorporated the notion that continents move. Wegener's theory contained features, such as the notion that the average elevation of the continents would increase over time, that simply aren't true. And plate tectonics supplies a mechanics for moving the continents (involving convection in the Earth's mantle), something that was conspicuously missing from continental drift.

The main lesson to be learned from Wegener's story, then, is exactly the opposite of the one the spinners of mythology want to advance. The scientific community is fully capable of abandoning a lifetime's worth of belief and adopting a new outlook provided there is enough data to justify the change. The fact that we don't accept ESP, UFOs, harmonic convergences, and the like arises from the fact that there isn't enough data to support them, and has nothing to do with the close mindedness of the scientific establishment.

It's a nice thing to remember next time you are confronted by a New Ager at a party.

James Trefil is Clarence J. Robinson Professor of Physics at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. This and other commentaries by scientists can be found on the Physics Central website: www.physicscentral.com.

©1995 - 2024, AMERICAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY

APS encourages the redistribution of the materials included in this newspaper provided that attribution to the source is noted and the materials are not truncated or changed.

Associate Editor: Jennifer Ouellette

November 2003 (Volume 12, Number 10)

Articles in this Issue