March 1882: Publication of Étienne Léopold Trouvelot's Astronomical Drawings

The rise of astrophotography in the late 19th century eventually revolutionized our ability to accurately map the night sky. Around the same time, a French artist and amateur naturalist with a passion for the heavens created a stunning series of hand-drawn astronomical illustrations of the Sun, Moon, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, among other objects. Étienne Léopold Trouvelot, who so loved solar eclipses, would see his work eclipsed by an emerging technology. But the beauty of those exquisite drawings is still entrancing people today.

Born on December 26, 1827 in Aisne, France, very little is known of Trouvelot’s early life. But he was either forced to flee or was exiled from France in the wake of the coup d’etat in 1852 that brought Napoleon to power. By 1855, he had emigrated to Massachusetts, working as an artist to support his family. He also showed a strong interest in natural science, joining the Boston Society of Natural History.

That interest in natural science didn’t mean he had a gift for experimental research. In fact, his earliest attempt at amateur entomology proved disastrous on an historic scale. After moving his family to Medford, Massachusetts, Trouvelot decided to raise about one million Polyphemus silkworms on the five acres behind his house. The native species’ growth is largely kept in check by natural predators and Trouvelot didn’t think the worms produced enough silk.

So sometime in early 1869, thinking he could increase silk production, he brought back a collection of gypsy moth eggs from a European trip. As bad luck would have it, a strong breeze one night blew the imported eggs into the wild. The consequences of this would not become apparent for 17 years, when gypsy moth caterpillars invaded the entire neighborhood in the summer of 1886. The infestation eventually spread to the entire state and the gypsy moth remains a despised invasive species to this day—all thanks to Trouvelot.

Fortunately, Trouvelot’s interests turned to the night sky, apparently inspired when he witnessed several spectacular auroras. He started sketching what he saw, and those sketches caught the attention of the director of the Harvard College Observatory, Joseph Winlock, who brought Trouvelot onto his staff in 1872, igniting the artist’s passion for astronomy. Trouvelot created hundreds of sketches based on his observations through the observatory’s 15-inch refractor telescope, and these in turn became a collection of 35 plates, some rendered in color.

Wikimedia Commons

Étienne Léopold Trouvelot

Wikimedia Commons

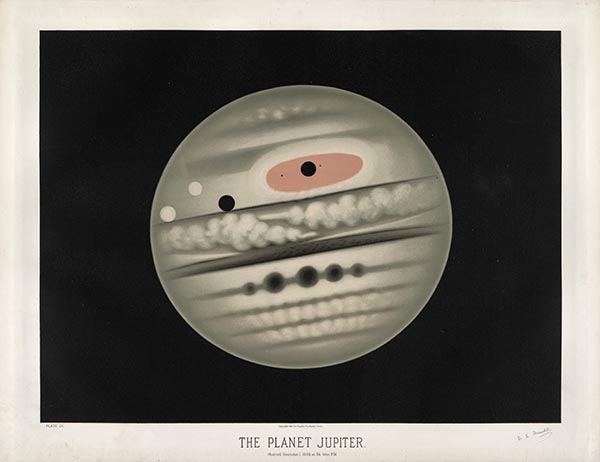

Trouvelot's drawing of Jupiter

His engravings of the Sun were particularly noteworthy, capturing sunspots and solar flares in exquisite detail. In 1875, Trouvelot discovered so-called “veiled spots,” which he thought were a variant on sunspots. And he embarked on an ambitious project to create a series incorporating his observations of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The idea, he wrote, was to “represent the celestial phenomena as they appear to the trained eye and an experienced draughtsman through the great modern telescopes.”

He started fixing a ground glass plate, or reticle, to his telescopes, engraved with a grid of squares. Images would be projected onto the grid, and he could make more accurate drawings on paper ruled with a similar grid. Although astrophotography was developing rapidly around this time, Trouvelot was convinced that “a well-trained eye alone is capable of seizing the delicate details of structure and configuration of the heavenly bodies, which are liable to be affected, and even rendered invisible, by the slightest changes in our atmosphere.”

He was, of course, wrong about that. Astronomy libraries and observatories were initially eager to purchase his chromolithographs, but interest waned as astrophotography continued to improve, since actual photographs provided even more detailed and accurate depictions of celestial objects.

All in all, Trouvelot completed around 7000 drawings, using the facilities of several observatories. The best of the completed pastels was exhibited at the first World’s Fair in Philadelphia in 1876, along with Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, the first commercial typewriter, and the right (torch bearing) arm of the Statue of Liberty. But Trouvelot craved an even larger audience for his work. In March 1882, Charles Scribner’s Sons published Trouvelot’s scientific writings under the title, The Trouvelot Astronomical Drawings Manual.

“While my aim in this work has been to combine scrupulous fidelity and accuracy in the details, I have also endeavored to preserve the natural elegance of the delicate outlines peculiar to the objects depicted,” a humbler Trouvelot wrote in his introduction. “But in this, only a little more than a suggestion is possible, since no human skill can reproduce upon paper the majestic beauty and radiance of celestial objects.”

Trouvelot remained fascinated by the Sun for the rest of his life, and he was especially keen on solar eclipse, even traveling to what was then the Wyoming Territory with his son George in July 1879 to witness the eclipse, setting up their telescopes at a nearby Naval Observatory research camp. In 1882, after the publication of his manual, he returned to France to work with famed astronomer Jules Janssen, then director of the Meudon Observatory.

Back in Meudon, Trouvelot’s relationship with Janssen soured. He wrote to American friends about how much he missed “the purity of the American sky” and longed to return, particularly given his failing health. But it was not to be. Trouvelot died in Meudon on April 22, 1895. Craters on both the Moon and Mars are named in his honor.

Further Reading:

Herman, Jan K. and Corbin, Brenda G. (1986) “Moths to Mars,” Sky and Telescope 72(6): 566-568.

Onion, Rebecca. “Beguiling 19th Century Space Art Made by a Self-Taught Astronomical Observer,” Slate, January 21, 2015.

©1995 - 2024, AMERICAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY

APS encourages the redistribution of the materials included in this newspaper provided that attribution to the source is noted and the materials are not truncated or changed.

Editor: David Voss

Staff Science Writer: Leah Poffenberger

Contributing Correspondents: Sophia Chen, Alaina G. Levine

March 2021 (Volume 30, Number 3)

Articles in this Issue